I am going to deviate slightly from the topic at hand today and instead focus on my other great love, wine.

Sunday night I got back from fulfilling a long-term dream of cycling down the Côte d’Or from Dijon to Beaune. It’s around about a 50km cycle all up (taking into account avoiding the terrifying highway that google was very keen to send me along), making it the perfect two-day jaunt.

For those of you unaware but interested, the Côte d’Or is a limestone ridge in eastern France that is home to some of the most famous vineyards in the world, and makes many of the world’s most expensive wines. It is split roughly into two: the northern end, called the Côte de Nuits, is planted almost entirely to Pinot Noir, and the southern end, the Côte de Beaune, is planted to Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

I arrived in Dijon on Friday night, and after checking into my hotel room that smelled like stale cigarettes (vive la France), I went a-wandering. As it turned out, I probably could have spent my whole weekend in Dijon, which was charming af, but duty called and on Saturday morning I tore myself away from the markets and the cobbled streets and the mustard shops with mustard on tap (mustard! on tap!) and began to pedal my way south.

I spent the first 5km or so making my way through the industrial outskirts of Dijon, and then things began to take a serious turn for the vinous. First I tootled through the vineyards of Fixin and Marsannay before arriving in Gevrey-Chambertin – the first really famous village along the Côte de Nuits. After spending about 30 seconds flat riding through the tiny village (as it turned out one of the largest along the way), I popped out into the middle of the grands crus, at the base of Chambertin itself.

I’ve spent a good, solid year or so writing about Burgundy – pouring over books, scouring through tasting notes, noting down soil types – and I can say now with certainty that nothing actually comes close to standing in the vineyard itself. A book is a poor substitute for experience: getting an idea of just exactly how steep these vineyards are (more so than I thought), what the soil looks like, how warm and windy they are in early summer. I pedalled on past my first grand crus with a silly grin.

The road was easy going – just a little bit hilly and for the most part devoid of cars, apart from an old man and a young woman traveling in a maroon Jaguar. I rode through an array of tiny, sleepy villages whose names I have written out hundreds of times – Morey-Saint-Denis, Chambolle-Musigny, Vougeot.

My first proper stop of the day was in Vougeot, a village that did not have any cold drinks for sale anywhere (but then again, neither had any of the others). But what it did have was the Château Clos de Vougeot, a 16th century castle in the middle of the eponymous grand cru vineyard. I had not realised that the château was open to wander around in, and spent a happy and slightly incredulous half hour or so exploring the presses and cellar before pressing on.

After Vougeot was Vosne-Romanée, which is probably the most prestigious of all the villages (I speak only in terms of wine – the village itself was like a ghost town). I rode up the hill to Romanée-Conti, a small plot of 1.71 hectares that makes the world’s most expensive wine, and heeded the small sign that told me to please keep out of the vineyard itself.

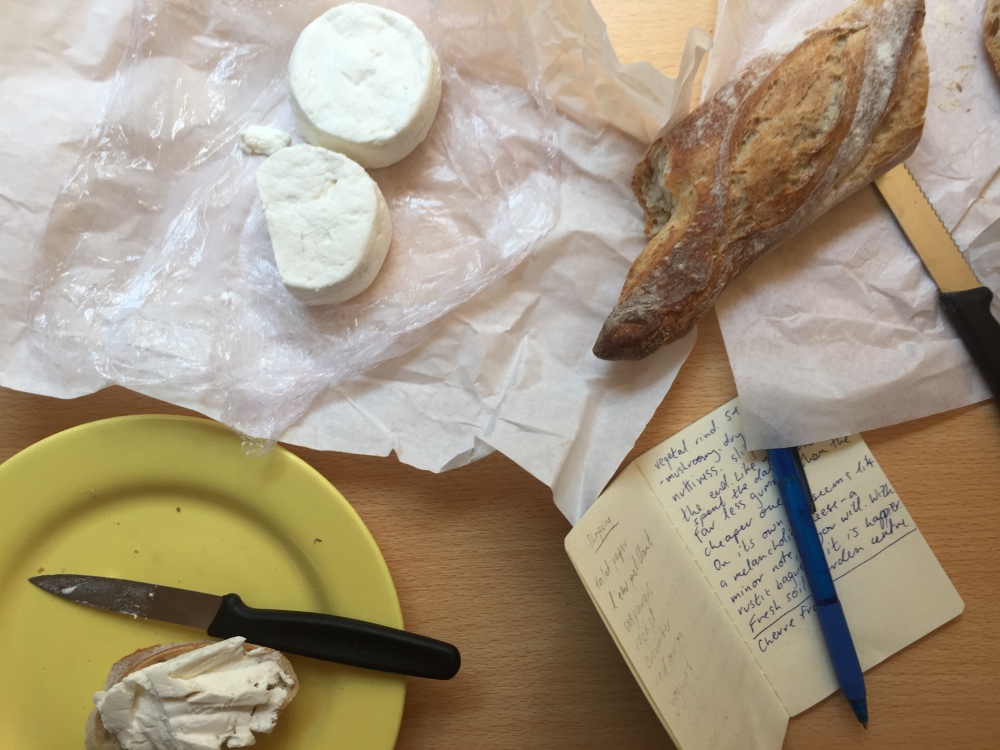

By that point I was parched and pooped and hungry, and it was with considerable relief that I found Nuits-Saint-Georges, the next village and my home for the evening, to be considerably larger than those that had come before. I grabbed some local Epoisses cheese and a baguette, and made my way to the hotel to lie in an air-conditioned room and eat very smelly cheese for a couple of hours. It was bliss.

That night, after exploring the cobbled streets of Nuits-Saint-Georges, I settled in to what turned out to be a four-course dinner at a local brasserie. I ate oeufs en meurette (eggs in a red wine sauce) and boeuf bourguignon, as well as cheese, and ‘cafe gormand’, which as it turns out does not just mean coffee, but coffee with a trio of desserts. After dinner, I trundled my tired, full, sunburned body back to the hotel.

The second day was a little more challenging than the first, because the nice, easy backroute I had been taking through the vineyards petered out somewhat, and I had to make the choice between braving the highway or taking a route through some wheatfields a la Theresa May. I chose the wheatfields.

The hill of Corton with its weird little toupée of woods eventually popped into view, marking the beginning of the Côte de Beaune, and I doggedly pushed my bicycle halfway up the hill before finding a nice, easy track again. From here, I zoomed down the hill into Aloxe-Corton, and from there, it was just a few more kilometres to Beaune, a medieval town complete with ramparts and a now-empty moat.

Once I arrived in Beaune, I gave my bum a much-needed respite from the bike, and wandered around the streets and museums and cellars while munching on quiche and icecream.

It was an incredible weekend. I sat on the bus back to Lyon and reflected on how these much-anticipated trips often disappoint – this one exceeded expectation, despite my exhaustion and my horrible sunburn and the fact that my final meal in Burgundy was a kebab eaten in a bus stop with an audience of pigeons. And because I was on such a high from my weekend, when I got back to Lyon I got this weird rush of “this is home” and felt super content.

A thing I have learned about myself in France is that given the chance, I can eat way more cheese than is possible to keep a blog about. A few cheeses have fallen by the wayside, potentially to be picked up again at a later date when they take my fancy again at the fromagerie.

A thing I have learned about myself in France is that given the chance, I can eat way more cheese than is possible to keep a blog about. A few cheeses have fallen by the wayside, potentially to be picked up again at a later date when they take my fancy again at the fromagerie.

I love a good dairy sandwich. When I lived in England, I was an enthusiastic purveyor of the Tesco meal deal, and in New Zealand, I tried the sandwiches at pretty much every bakery, home cookery and food bar in all of New Lynn.

I love a good dairy sandwich. When I lived in England, I was an enthusiastic purveyor of the Tesco meal deal, and in New Zealand, I tried the sandwiches at pretty much every bakery, home cookery and food bar in all of New Lynn.